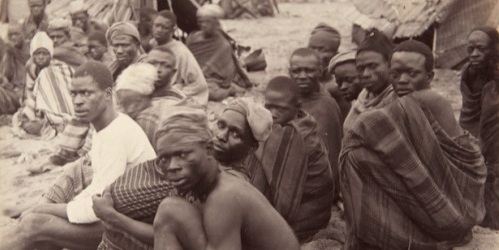

Slavery, the forcible commodification and holding of humans for the provision of labor lasted for about 350 years. While it did, about 12.4 million Africans were transported to the Americas to the benefit of the plantation societies there. During the reign of Obalokun Agana Erin, Alaafin of the Oyo Empire, it was recorded that the Alaafin sent messengers with presents to the king of Portugal or France with whom he had made acquaintance, but that the fate of those men were never known. Although a white traveler had shown up in the center of the Yoruba government as early as this time, the first certain contacts with Portuguese travelers to the west of present Nigeria was made in Lagos only in the 15th Century.

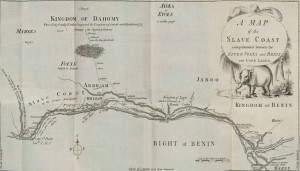

Prior to the commencement of slave trade, European adventurers engaged in the exchange of rudimentary items like pepper, gin, textiles, and woven clothes. By the second half of the 17th Century, trade relations had started involving the purchase of those who made the goods themselves as Europeans began arriving on the coast of West Africa’s Bight of Benin in significant numbers to trade in slaves for the benefit of their plantations in the Americas. The export of persons for work at Brazilian and Caribbean plantations was conducted mostly from West Central African coast.

As volume of slaves increased, activities spread to the Bight of Benin. Benin, Ijebu, Allada, and Oyo traders now transported slaves beyond the West African region or islands in the Atlantic. Lagos, being centrally located on the water route linking these kingdoms and the Oyo southern commercial termini, became an important center of the expanding trade. Although Benin showed little restraint, banning the sales of male slaves to Europeans, Oyo utilized the growing phenomenon as instrument of power. Focus soon shifted from Benin to settlements between Apa and Keta, which the Europeans, in recognition of its importance in the supply of labor to America dubbed the Slave Coast.

Following the incursion of the Fulani around 1817, the empire of Oyo had lost its adhesiveness, opening up an era of Civil Wars for which the rest of the century was characterized. Due to this wars and temptation of the commerce involved in the sales of prisoners or outright kidnapping, slavery had become instituted in the fallen empire. Lagos became an important slave port around this time, when the Bight of Benin supplied the bulk of West African slaves and it remained one of the few centers that persisted in the supply of humans north of the equator after the clampdown on the practice.

By 1821, Yoruba slaves had been freed to Sierra Leone, their ship intercepted by the British Naval patrol that was scattered in the sea to check slavery activities, which had become illegal by English laws since 1807 when the trade in humans was abolished. Liberated slaves began to trickle back from Sierra Leone in 1838 to find their relatives settled in relative safety in Abeokuta. Although these Sierra Leone returnees or their parents had been direct victims of slave trade, a number of them, as reported by Kristin Mann in Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, kept slaves on their return to Abeokuta and Lagos.

Slaves in the east were sometimes subjected to the most inhumane act, even though a very influential Igbo king-priest, Eze Nri Ewenetem who lived c.1728-1820 declared that they were human being and to kill one was an abomination. The official termination of slave trade in Eastern part of Nigeria paradoxically marked the beginning of a new era of cheap and abundant slaving. Ajayi Crowther in late 1850s stated that the accumulation of slaves at Abo, a Igbo area, was the prevailing ambition of the people who believed it to be a status symbol.

As news of emancipation of their kind in other parts of the Niger-area reached the Niger slave communities they began to rebel. In the Igbo town of Abarra Uno, slaves left to found an independent settlement at Abarra Ogada. The same occured for the town of Ossomari whose population was almost halved by 1928 with the mass migration of slaves to near site at Okpolodun Creek, or to join their now independent brethren in Abarra Ogada, in the western side of the Niger. Surviving impact of slavery in Nike, an Igbo village group was observed in the early 1950s by Professor Horton to be great. Freeborns abhor farm work, and hired migrant labourers, thereby reducing their own economic benefit.