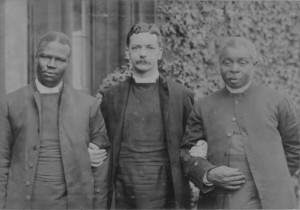

Charles Phillips was the 19th Century Head of the Church Missionary Society in Ondo, whose parents were Yoruba Sierra Leonean returnee. At Ijaiye Charles’s father, known by same name, was a church catechist. Charles Phillip, born in 1847 to Egba parents is remembered for his effort in negotiating a truce as an emissary of the British government in persuading Ibadan and Ekiti to put an end to the Kiriji War. He is also credited with civilizing the people who he pastored in the ways of the British, supervising, for example, the introduction of cocoa farming to town, and crusading against human sacrifice that was a feature of the Oremafe festival in Ondo. Although he wasn’t as fortified with a college degree like his contemporary African bishops; James Johnson, or Isaac Oluwole, Phillips was in the class of these fellows who left records of morality and dedication.

Charles Phillips was like his father, a catechist, but he served in the Breadfruit Church in Lagos. Around this time, the CMS under which he now served as a deacon was involved, through the Lagos colonial government in a diplomacy at Ode Ondo where anarchy was looming with the deposition of the unpopular monarch of the city-state. After helping to bring order, the reinstated Osemawe invited the church to set up its mission in the new Ondo, which is also being opened to business with the opening of the alternative road from Lagos to the Yoruba interior, then called the “East road”. This is because Ijaiye, was at war with Ibadan, and the kingdoms of Ijebu and Egba, taking sides against Ibadan, had appropriated the passage of their roads, blocking trade and free movement to the interior.

Charles Phillips became head of the Ondo church in 1877. His skills in settling the terms agreeable to warring parties in the EkitiParapo war without compromising the prestige of either was commended by the British House of Commons. Phillips clearly dreamed of more, and like Bishop James Johnson, on whose deputation he secured his celebrated accord in Ekiti, he often decried the decadence of his day. He believed in the magical effect of the white man and pleaded the dispatch of white missionaries who he hoped would set good example of the Christianity he tried to preach. Unlike Johnson, Charles was circumspect about the native bishopric campaign of the former. When the need for a conciliatory gesture towards nationalists who wanted an indigenous bishop in succession to Ajayi Crowther arose, he was made Assistant Bishop of Western Equatorial Africa, a position derided by Johnson as “half-bishop”, on which he remained till his death in 1906. Although he was branded, together with Oluwole who was also “half Bishop” as a traitor of the Negro race for accepting to be appeased, Charles’ own argument had been that the African was to be blamed for the erosion of his culture. During his headship of the Breadfruit church, he had contributed to the Great Debate of New Africa and the African Renaissance by writing a play published in 1915, Aso Ile Wa, meaning, Our Native Dress. In the play, he showed that there wouldn’t have been room for the erosion of culture if the black man had stuck to his’.

Phillips was one of the most enthusiastic advocates of agricultural innovations of his day. His diaries and papers contain numerous references to his exploits as one who planted and propagated new crops in Ondo and beyond. Also, Phillips participated in the literary awareness of the late 19th Century with his record of Ondo history, and illustration of its elaborate chieftaincy system. The celebrated Master of Music at the Christ Church of Cathedral, Thomas Ekundayo Phillips was his son.