Apotheosis is the promotion of an individual to a godlike status. The term in Nigerian discourses is dominantly used in religion and in politics to denote respectively, the divinization of a hero, leader, or person acclaimed to possess spiritual power, and public office holder who enjoys large following in life and in death, hence having their imperfections glossed over.

Humans have always been deified as Orisa, as Orunmila, the Yoruba philosopher who lived around 500BC in Ile-Ife said. In one verse of his Ifa literary corpus, Eji-Ogbe, he or the corporate entity which represented his ideas affirmed Orisa-Ala was once a human being. When he brought blessings to the world, men began to worship him as god. Ogun was once a human being, Sango was once a human being. Orunmila himself is being characterized by many western educated ethnologists as a “Yoruba god of wisdom,” an otherwordly being who was never human. This is inspite of the unambigous designation that Orunmila historically carries; Baba Ifa, meaning, father or patron of the the geomancy, and never “god”. Professor of African Philosophy, Sophie Oluwole explains that this general misunderstanding is derived from the Greek notion of gods and godesses, in which members of the pantheon are imagined to operate between the earth and celestial world. This, in Oluwole’s argument, is clearly at variance with the Yoruba concept of Orisa.

Oftentimes leaders who display unusual abilities are deified. Onoja Ogboni, the belligerent hero of the 18th Century Igala kingdom was said to be a giant who possessed six fingers and toes. An entire village would flee, they said, at the sight of him. Exaltation would come for the Owu war captain, Balogun Anulugbon in death after he had promised to save his people in war if they came to his grave side to shout “war”. When in 1892, a very large body of enemy army allies laid siege against Owu, the unbelieving people were left with no choice than to put Anulugbon’s promise to test. Subsequent claims that the dead war captain appeared with a long sword killing indiscriminately may have been due to the overwhelming force with which enemies descended on the field, confusing would-be chroniclers on the actual occurrences at the front.

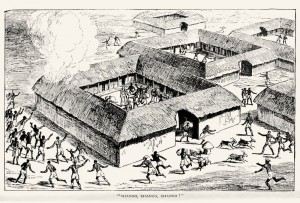

In modern times, charismatic figures have commanded the followership of people who saw them as superhuman. Garrick Sokari Braid, a member of the CMS in Bakans, New Calabar, described by Bishop Oluwole Johnson as being full of zeal and energy for preaching indulged in pyscho-physical faith healing practices which apparently brought him many admirers and followers. Garrick’s movement was described by the Times of London as a dangerous pseudo Christian movement spreading throughout southern Nigeria and of such a dangerous character that it upset the normal course of administration in the Delta. Braid proclaimed himself Elijah II and preached that power was soon to pass from the whites to the blacks. It would not be long before he got jailed. British authority viewed Braid movement as a kind of negro mahdism, but the real mahdists would surface later in the century when in Lagos, a son of Joseph Odumosu who was a well-known socialite, called Jesu Oyigbo would declare himself Christ, and the missing of the Trinity. Jesu Oyigbo converted into his college of regeneration, top middle-class educated elite in public and private sectors some of who chose to live in his boarding house empire as his disciples. He is also known to have utilized his followers for the benefit of his business enterprises, which included hairdressing salons, restaurant, and a bakery. Other persons with implicit or clear claims to divinity include the Olumba Olumba Obu of Calabar and Sat Guru Maraji of Ibadan. In the 1980s, a Cameroonian resident of Kano, Muhammadu Marwa amassed a large following through his radical teachings, which often stood apart from mainstream Islam. Maitatsine, or “one who curses,” so named because of his love for reeling curses on non-believers, was said by historians to have claimed himself to be a prophet. When the spate of clash against government authorities increased, Marwa’s influence was arrested in a raid that ended his life and that of some hundred followers.

While ancestor worship in whatever form remains a feature of African reality, scholars like Musibau Oyebode of the National Open University are apt to critique the model through which worthy ancestors or candidates for apotheosis is decided. Oyebode showed no hesitance in categorizing Sani Abacha as unworthy, and Obafemi Awolowo as worthy, in this regard. In Awolowo’s case, a stiffer critique by Chinua Achebe in 1987 cautions against his deification at the national level, as he was, in Achebe’s opinion, a hero only of a session of the country. Seemingly conforming to Oyebode’s standard is the case of the 15th century Edo market woman, Emotan, whose reputation as a care giver of village children and loyalty earned her a deification in death by the decree of Oba Ewuare.

The overriding subject of discourse on apotheosis among Nigerian post-independence public scholars has been the deification of contemporary leaders, of which they are unequivocally critical. Phenomenon akin to apotheosis, but which are more correctly Clientilism; the acquisition of public loyalty through philanthropy, Godfatherism; the reliance on the patronage of an overbearing political figure, and Gerontocracy; the near deification of living elders, has been alleged to have sustained corruption. This is because adulation of important public officers, eminent persons, and indeed anyone who shows themselves important to their lives often goes to the extreme. Elements of apotheosis is to be found in popular music of Asa, who posits in Mother that there is no deity on earth that can be likened to a mother. Lagbaja proclaims the apotheosis of the late Fela gleefully in Abami, “The weird one has become a deity.” Abiodun Bello of the University of Lagos concludes the Yoruba attitude to their ancestors is preserved in these examples.

While apotheosis is a commonly occurring phenomenon in pagan Nigerian religions, understanding of the divinity of Christ was never syncretized with old attitudes. Oshoffa interpreted the pyramidic fashion of the processional candle lighting ritual in Celestial Church liturgy to denote the gospel of Christianity; that the only true God descends to bring man up unto himself. This follows the rule of Christian theology which adopts the term theosis rather than apotheosis in illustrating the status of Christ as the pre-existing God who undertook human existence.