Tribal marks are scarifications that are done on the body in several Nigerian ethnic communities. Mostly seen on the cheeks, the marks are also made on the forehead, chin, abdomen, back, arms and hands. Presently considered by many people as a barbaric and unseemly practice, tribal marking was done in the past for good reasons and presently it is only practiced by few indigenous people of Nigerian tribes.

Originally, tribal marking was developed as a means of distinguishing between people of different tribes, families or lineages. This was necessary because of inter-tribal wars that were prevalent in those times and also because of ancient traditions that forbid relationships especially marriage between particular tribes or families. However, not all body scarifications are ‘tribal marks’. Over time, the scarifications became indicative of other things, for example, the Elili marks of the Igala tribe are given only to the first child of a family. Among the Yoruba people, especially in Oyo, two marks on the arm were a symbol of royalty.

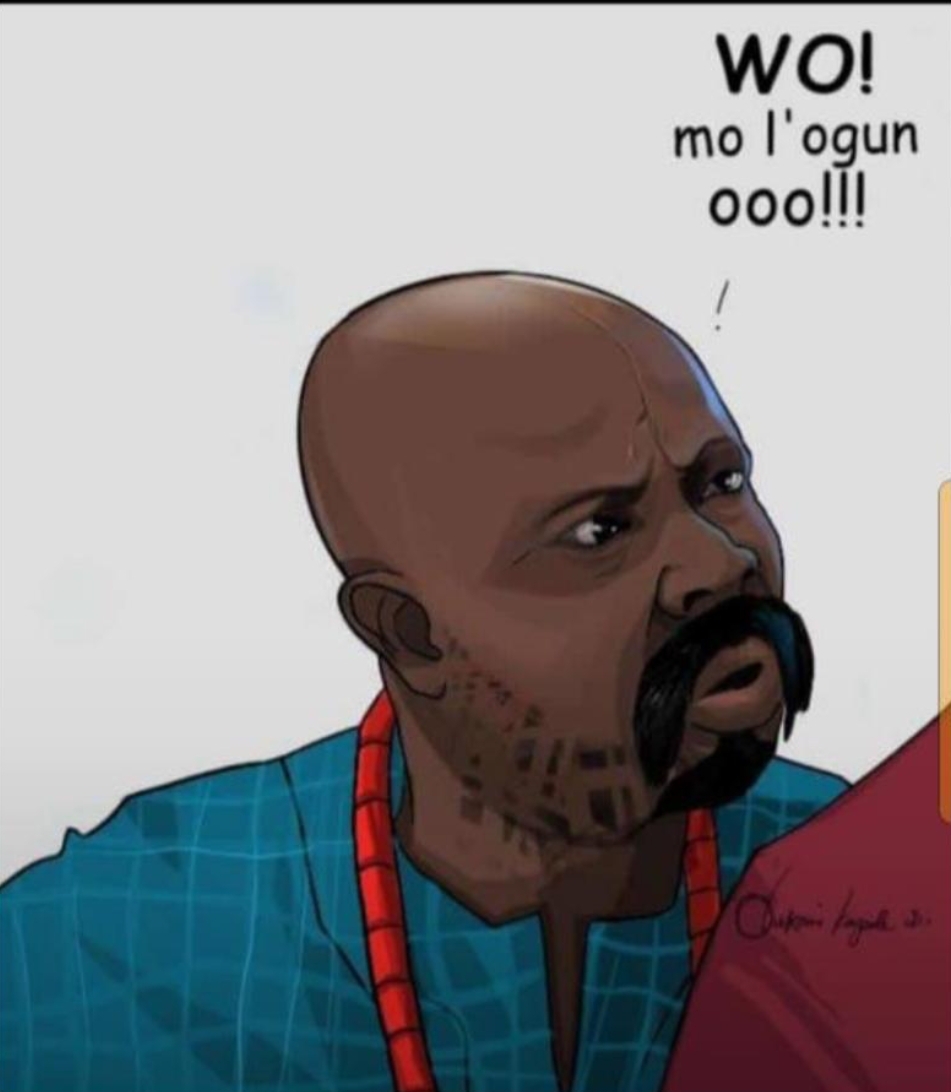

According to legend, Sango, who was once the Alaafin (king) of Oyo, sent two of his slaves to carry out an important task. Upon their return, Sango found that one slave had carried out his part of the work commendably while the other had not done what was required of him. The King therefore rewarded the loyal slave with high honours, but commanded that the other slave be given a hundred and twenty-two razor cuts all over his body. Sango’s gruesome order concerning the unlucky slave was carried out, but when the scars healed, they gave the slave a very adorable appearance, which greatly took the fancy of the king’s wives. Sango therefore decided that cuts should in future be given, not as punishment, but as a sign of royalty, and he set the pace by asking to be marked. He however could only bear two cuts, and since then, two cuts on the arm have been a sign of royalty.

Some marks were also given as memorials to late members of a family. A child that was born after the death of a Yoruba family head was usually given the same marks that the head had as a tribute to the late man. Children could also be given the same marks as their late grandparents. In some tribes, marks are signs of valour and military prowess; few marks mean that a man has conquered only few enemies while numerous marks signify a great number of conquests. Marks were also given to physical handicaps such as the deaf and the dumb. This facilitated their easy and quick identification especially when they needed help in public.

Other marks signify nothing in particular but are just means of beautification. An example is Soju which is borne by Yoruba women on their arms, breasts or abdomen. Unlike most other marks, Soju does not form scars; it rather appears as black markings on the skin. Whatever the purpose, body scarification in the past was a sign of affluence as it was then too expensive for common people to afford.

The Yoruba people of South-western Nigeria perhaps have the richest cultural heritage as far as tribal marks are concerned. The marks borne by Yoruba people include Bamu, Keke, Abaja, Pele, Gombo, Ture and so on. Abaja consists of four horizontal lines on each cheek; Pele is made of three vertical lines on each cheek, while Ture is made up of three long horizontal lines and three short vertical lines- six in all- on each cheek. Four long vertical lines drawn almost from the scalp and curved into four perpendicular lines on each cheek constitute Gombo. However, there are variations in these patterns from one Yoruba community to another; the lines may vary in number or length. For the Ondo people of Ondo State, the typical Ondo tribal mark is one long vertical line on each cheek. According to tradition, Ile-Ife people do not bear facial marks.

Tribal marks are usually given during infanthood so a person does not really decide for himself to be marked or not. The marking is done by professionals (who usually also undertake circumcision) by incising the skin with a sharp knife and rubbing in a black paste made from charcoal. The paste is responsible for the consequent permanent scarring. Soju is an exception as it is done for a woman out of her own volition and the marking is made with a bunch of needles and not a knife. Apart from the ones that had been discussed, some marks were given as native medicinal therapy to manage convulsions, chicken pox, and occultic attacks. Such marks can be made on any part of the body but they are smaller and less obvious than tribal marks. These marks are called gbere in Yoruba.

In some cultures where crocodile hunting is an important form of tournament, contestants have short strokes incised on the whole of their backs and limbs in the similitude of a crocodile’s scales. This is believed to shield them for attack from crocodiles as they partake in the tournaments.

Nowadays, the culture of tribal marking is seen by most people, especially in civilized Nigerian societies as outrageous and barbaric and there seems to be no reason that is good enough to justify the practice. Tribal marks are often described in terms like “ugly deep grooves” and “scary facial marks”. People who bear tribal marks are often the subject of jokes and they easily get nicknames like “lion fighter”, meaning their marks are scars of a lion’s claws. As a result of the ridicule associated with tribal marks nowadays, only few tribal-marked people are proud of their marks; most, especially youths, would rub them off without a second thought if they could. It is obvious that body scarification has already taken a bow in most Nigerian societies and for some people; the Western practice of tattooing has taken its place.