Itsekiri are a small ethnic group in southern Nigeria, numbering just over 30,000 in 1952. Due to the position of their homeland- western area of the Niger Delta and the estuary of the Benin River, the people in in the 18th century became wealthy as middlemen between European traders whose ships lay off the habour of the Benin River and palm oil producing Urhobo people in the interior. Though historian William Moore gave the name Itsekiri as being of the man who Ginuwa, son of Nuwa, who was the unpopular Oba of Benin in the late 15th century met in his place of rest, Jacob Egharevba says the name by which the people is today known, Itsekiri, means “I reached where my father sent me.”

The kingdom of Warri, as the Itsekiri calls it, was founded when Ginuwa was set forth, according to the precept of the Benin chief priest’s divination, in the company of 70 first born sons of the Benin headsmen. These headsmen or chiefs, alarmed that their sons had not returned to Benin after years, sent warriors to fetch them back. Ginuwa and his now loyal or bewitched company were pursued to Ugharegin, Efurokpe on the Jamieson River, Amatu, Oruselemo, Ijala, and finally, Ode Itsekiri, commonly called Big Warri which is some four miles from the modern town of Warri. The territory, according to Itsekiri historian, William Moore, was inhabited at this time by Ijaw, Sobo (Urhobo), and the Mahin people.

In 1516, while at Ijala, Ginuwa encountered Portuguese explorers who presented him with cassava plants for cultivation and showed him the process of manufacturing starch, farina, and garri with cassava roots. The Itsekiri nation thereafter adopted cassava plant derivatives as their staple food. By the year 1588 the Portuguese had established trading stations at Warri and Gborodo for the export of slaves, and items like spices, and pepper from Benin City. Elephant tusks were traded on occasions too.

Portuguese incursion

Roman Catholic missionaries of the Spanish Capuchin Mission arrived in Warri to proselytize the Christian religion in the mid-17th century with the influence of Anthonio de Mingo, the mulatto Olu of Itsekiri who was a staunch Christian. The mission was to wind up however in four years with the death of Anthonio. Asides the apathy of the Itsekiri towards the missionaries and their religion at this time, another reason given for the failure of the 17th century mission was the difficult diplomacy between Rome and Portugal, toughened by the rivalry between Spain and Portugal, hence the lack of support for the Spanish mission. Portuguese residents in Warri at this time paid more attention to trading- more specifically the trade in humans, which they conducted quite effectively with the Itsekiri nation till 1837. In that year, vessels from the British in whose land slavery had been outlawed earlier in 1807 challenged the naval power of Portugal. Waters around and within the Warri kingdom was cleared of Portuguese ships through a fierce action and they were chased down the Benin River in the direction of the sea.

Rise of Nana

In 1848, servants in the houses of princes, Ejo and Omataye who were sons of Olu Akengbuwa staged a revolutionary act of rebellion which would lead to a major dispersion of Itsekiri population to various places in the Benin region and creeks around Warri. Killings of adult sons of the house of Akengbuwa and the anarchy that followed had been instanced by the death in quick succession of the Olu and his first son, followed by the second. The frustrated servants of the princes, called Olurokos, decided no one would get to the stool of the Olu, hence resolved to make the kingdom ungovernable. Now, trade in the Benin River and the Warri area was being regulated under common agreement supervised by the British, and Governors were selected to collect a kind of tax called comey from traders. During Akengbuwa’s reign there were nine persons succeeding to the position. With his death, the ensuing civil disturbance, and the decline of the kingdom’s capital came an era in which the governors had the executive power in commercial and political affairs. The fourth to occupy the newly evolved office, Nana Olomu craftily appropriated the monopoly of Palm Oil trade in the area to acquire even greater wealth than his father who was the governor before him.

1884 Treaty

On 26th August 1884, a treaty was made between British consul, Hewett and the Itsekiri chiefs which was within two days transmitted to other important persons of the Itsekiri nation in Big Warri, Usele, Ubeji, Ifie, Ugbori, and other villages. With this treaty, Itsekiri became part of the British protectorate in southern Nigeria. Also, the freedom of the subjects and citizens of all countries to carry on trade in all parts of the territory were asserted. Tension mounted with the British as Nana, the Itsekiri chief and governor thickened his influence in the area, hence his dominance in trade, sometimes in disregard of the new statutory requirements. When in 1894 he refused the British request to release Urhobo captives with whom he recently had trade dispute, the opportunity was provided to have his growing power nipped and the kingdom which he had built at Ebrohimi overridden. With the fall of Nana and his exile to Accra in Gold Coast, now Ghana, came the rise of a scion of a rival family who had felt slighted with the rise of the former, ten years before. Strategic assistance rendered to the British by Dore Numa, who was son of Nana’s archenemy was rewarded with the expansion of his authority to include the entire Warri province. Though vilified for his role in not just the capture of the great Itsekiri figure, Nana, but also in the Benin Expedition, history tends to reward him for his faithfulness to the inevitable trend of British modernity. The size of the office which he occupied for almost four decades would be transferred to the first Olu in 88 years, Emiko Ikengbuwa, who was styled Ginuwa II in 1936.

In the twilight of the colonial era, the Itsekiri, constituting Warri province, formed part of the eight divisions of the non-Yoruba part of the Western region, to be later named the MidWest region. Drawing from the strength of Itsekiri foundation story and allegedly due to political considerations, the Awolowo administration in 1952 formalized the designation of the Itsekiri leader as Olu of Warri, with a reaction from close ethnic knits who felt slighted with the seeming imposition of another’s traditional authority. This development would lead to the Warri crisis and the political matrix that will manifest in the creation of Delta state of Nigeria.

Itsekiri today

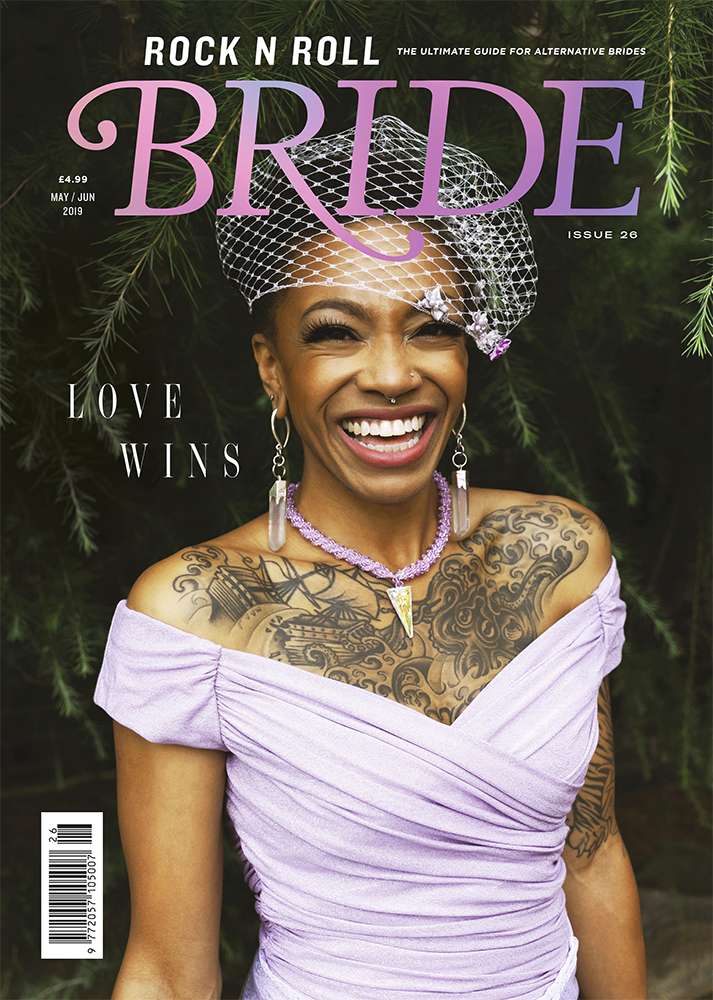

The Itsekiri, predominantly Christian with a traditional wear that is imitative of the Europeans with whom contact was made so early in their history, have a young generation which often speak English as first language. Even though it is established that the Itsekiri people originated from Ile-Ife before choosing Benin for their homeland, the Itsekiri language is strikingly similar to either Ekiti, Igara, or Mahin and in author William Moore’s time (1920s) was taken as a dialect of the Yoruba language. The Itsekiri social structure is however very different from that of most contemporary Yoruba or Edo speaking people. Customarily, both men and women tie a George wrapper around their waists. While men wear a long sleeve shirt called Kemeje, women wear a blouse. Like the Urhobo, or the Ijaw, men put on a hat too. The people, having high literacy rate, are numbered today in almost a million and call three local governments of Delta states, Warri South, North, and South West home. They are also found in large numbers in parts of Edo and Ondo states.